- Home

- Zoe Deleuil

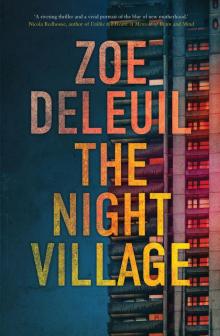

The Night Village Page 9

The Night Village Read online

Page 9

Soraya’s face softened, and her formal tone loosened a little. ‘Brixton is very nice. Well, not nice, exactly, but a good place to live. I actually have friends down there who may have a room going.’

The baby started to fuss on her lap, and she handed him back to me quickly, wiping her hands on her skirt.

‘Really?’ said Rachel. ‘I haven’t checked it out properly yet, but it sounds good, like there’s a lot to do, live music, stuff like that.’

‘My friends live up at Poet’s Corner. It’s lovely there. Although lots of prams,’ said Soraya, rolling her eyes.

‘What, lying around on the footpaths?’ I asked.

‘No, stuffed full of screaming babies. Nappy Valley, we call it. Sorry, Simone, but it’s true. You’re one of them now. A mom. You’ve crossed over.’ She blew me a kiss and laughed. ‘I still love you, but you have.’

‘I have not! Don’t say that.’ I knew she was joking, but at the same time I recoiled at the thought of disappearing formlessly into the world of motherhood, so sanitised and sleep-deprived and dull, and leaving her behind in the real world.

‘So where are the good places to go out?’ said Rachel.

‘Well, Brixton Academy, obviously. I was there the other night. The Ritzy Cinema, lots of restaurants, bars, the markets – depends what you’re after.’

‘And where do you live, Soraya?’

‘I’m in Vauxhall. A place called Bonnington Square.’

‘Oh, I think I read about that in a magazine. Is that the place with the garden with all the oversized tropical plants?’

‘The Dan Pearson one, yes it is. And there’s Bonnington’s, the café. They only serve one meal a night, the same one to everyone, vegetarian. It’s quite famous, in an insider’s kind of way.’

‘Speaking of the same meal every night, I’m going to feed the baby.’ I said it jokingly, but Rachel looked at me like it wasn’t funny at all, and Soraya didn’t laugh. She seemed a bit distant, and if Rachel hadn’t been there I could find out what she’d been up to since we last spoke a few weeks ago, let her know that even though I had a baby, she was still important to me, that nothing had really changed. But Rachel was there, and she was quietly taking over.

‘I’d love to come and see that garden, and the café.’

‘Oh you should. It’s beautiful.’

‘Really?

‘Sure.’

‘Today?’

‘Well, I was going to spend some time with Simone today, and give her a chance to rest.’

Rachel was scrolling through her phone. ‘I’m just looking at the Ritzy. There’s actually a movie I’ve been wanting to see that’s on there. Gravity. It starts at two. I’ve kind of been cooped up here.’ She glanced at me apologetically. ‘Not that I mind, of course!’ She showed Soraya her screen.

‘Oh, that one! It looks good.’

Soraya loved movies and I thought back to the last one we’d seen together, when we’d laughed so hard the people in front of us had moved seats.

‘You should go, Soraya,’ I told her. ‘Make the most of your day off. There’s not going to be much happening here, honestly. I’ll have a nap when the baby does.’

‘Really? I wouldn’t say no to a lazy afternoon movie.’ She fake-coughed delicately, covering her mouth. ‘I’m technically off sick from work, but a movie won’t be too taxing.’

Rachel looked at me. ‘Will you be okay here? Or do you want to come along with us, or …?’

Panicked thoughts crammed up against each other. Can you take a baby to a movie? Do I want to take him underground? How do I get the pram down the escalator? What if there’s a bomb scare? Or someone sneezes on him?

They both looked at me, and I knew their afternoon would be far more relaxed if my needy bundle and me weren’t a part of it.

‘Oh, I won’t. I went for a big walk yesterday so I think I’ll stay home today.’

‘Well, if it starts at two we should probably get going. I can text my friends about the room and maybe we can drop by there first.’

‘Oh – that would be amazing. Thanks Soraya!’

It wouldn’t actually be amazing, I thought to myself bitchily. Helpful, yes. A good use of time. But amazing was a bit of a stretch.

They were both looking at me oddly. Had I said that aloud? What was wrong with me? Soraya had come to visit, brought me thoughtful gifts, and I was fuming and jealous and miserable.

Rachel was still playing with her phone. ‘It says there’s a good cocktail bar near there. The Rum Kitchen? Have you been?’

Soraya glanced at her screen. ‘I have. There’s a better one close by. We can go there after.’ She rolled her eyes at me. ‘London newcomers, right? Always trying to tell you where you should go. You can leave the cocktail bars to me, sweetie.’

‘Okay, Soraya.’ Rachel smiled at me. ‘Will you be okay here, Mummy?’

I had struggled to get used to this in the hospital, when midwives would say, And what does Mum think? and I’d look around, wondering why they thought my mother was with me, before realising they were referring to me, that I was the mum. It was fair enough, easier than memorising every patient’s name, but coming from Rachel it sounded a little patronising.

‘I’ll be fine.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes, honestly, I’ll probably have a sleep,’ I said, imagining cool, sour cocktails and smoothly melting ice cubes and sitting back in a dim, restful theatre on the red velvet seats of the Ritzy with nothing more to do except watch scenes appear in front of me.

After they left, as I fed the baby again, I thought back to when Soraya and I first worked together at Dove Grey, before she was headhunted and took up a role as features editor on a rival magazine. She was the chief subeditor, and I was the lowly editorial assistant, and one Saturday she came over and we went out for lunch, and then she invited me to a party, some friend of an acquaintance of hers, and I said yes. And then I remembered I had left my new gold skirt at work, and I really wanted to wear it, so Soraya suggested we drop past the office on the way to collect it.

When we got there the security guard recognised Soraya, of course, because she knew everyone, and we made our way to the office, a huge basement space of low, sagging ceilings and fabric-covered partitions, always strewn with half-eaten packets of Hobnobs and straggly indoor plants drying out in the overheated air.

Just as we were about to enter, we heard someone thundering towards us, down the overpass. Clutching each other, we turned towards the sound.

It was the security guard. ‘Stop! I just remembered – it’s been sprayed in there for pests. No-one is meant to enter for twenty-four hours.’

I gasped with more drama than, in retrospect, the situation warranted.

‘What do you need in there?’

‘A skirt.’

The guard looked at us blankly. It sounded ridiculous. But we’d come all this way and my beautiful gold skirt was right there. I could see the navy paper shopping bag on my chair. And I really wanted to wear it that night.

Soraya saw my face, took a huge breath of air and blocked her nose, and before the guard could stop her, thundered into the office and retrieved my bag.

She exhaled and handed me the loot.

‘Sorry, Max,’ she said to the guard, who looked like he was trying not to laugh. ‘I’ll buy you a coffee on Monday.’

And then we went to the party, and shared a bottle of wine, and I woke up to her dressed in my beach towel and frying eggs in my flat-share kitchen, making it feel like home for the first time since I’d moved in, three weeks earlier, in a minicab with my suitcase and a clutch of bulging plastic bags.

Rachel was out for the rest of the day, and as if disturbed by the sudden quiet, the baby began to howl up and down the walls. By five we were barricaded in our bedroom, the curtains drawn and the lights low, the relentless noise making my head pound, pinning me to the bed as my eyes roamed around every dusty corner of the room, where discarded clothes a

nd damp towels lurked and multiplied. I tried calling Paul a few times to ask if he could by any chance come home early, but his line rang out. The pale yellow roses sent by my work colleagues seemed to tremble with the volume of the crying, and dropped their cupped petals onto the bedside table until every stem was bare. Eventually, in an effort to steer the day into happier territory, I retreated to the bathroom, scrubbed the tub and ran a warm bath.

The sound of the water and the steamy warmth seemed to soothe the baby, so I fed him sitting cross-legged on the floor, then undressed him while he was drowsy and full, wrapped him in a towel and undressed myself, then picked him up and carefully lowered myself into the water. His umbilical cord still looked raw against his poddy belly. But he lay limp on my chest, no longer crying, and as I relaxed and closed my eyes our shared agitation seemed to fall away.

It was so quiet, with only the pipes of the building murmuring through the walls, and I began to soften and drift, thinking of sleep, of owls and dark caves and everything drowsy and still.

And then I was wide-awake, adrenaline pumping, and lifting us both out of the tub, appalled at my own carelessness. A new image to add to my night-time horror screening: waking up in a lukewarm bath with the baby slipped under the water. He cried as the cold air hit his body, but I wrapped him in a clean towel, then dressed him in a tiny nappy and a grey sleep suit and breathed him in for a moment, thankful for his body, as healthy and active as a beehive beneath that poreless skin, before taking us both to bed.

We were still there as night fell, when Paul’s key rattled in the lock. I heard him on the phone, then a soft knock at the door and he came into the bedroom with bowls of Thai food, warm and salty and delicious, and we ate it together in bed, watching a movie on his laptop, exactly as we used to, but with the baby safe between us.

8

The baby woke through the night and each time I fed him and fell straight back into blankness, clutching at sleep like it was a blanket that might be pulled away without warning, leaving me cold and exposed.

At some point Paul wandered off to sleep elsewhere – apparently one of his work colleagues with children had advised him that there was no point everyone being tired – and I lay there, listening as a key fumbled at the door for a long time, and someone stumbled in. The bathroom light went on outside my door, and I heard Rachel, swearing and exclaiming loudly. Eventually, I got up and went to the open bathroom door, blinking at the bright whiteness. She was standing in front of the mirror, teetering slightly on her heeled boots and supporting herself with one hand on the basin. With the other, she appeared to be pinching her squinting, red eye, again and again.

‘Fucking hell! Come on! Fuck!’

The cold tiled room was sharp with the smell of alcohol.

I blinked. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Oh, Simone! You scared the crap out of me. Trying to get my stupid contacts out. We ended up at the Notting Hill Arts Club.’

‘But you were going to Brixton?’

‘It’s a long story. I can’t get them out. If I go to sleep with them on I’ll wake up and my eyes will be glued shut.’

Her eyes, so red, met mine in the mirror. My Isabel Marant silk scarf, the one Paul had given me on one of our early dates, was wrapped around her neck, but I noticed for the first time how bedraggled she was, with her scuffed boots and a hole in her shirt. She looked like a neglected teenager, although she was in her twenties like me.

‘Are they still in? Maybe they fell out.’ I said.

She rested a finger on her left eyeball and moved it slightly, then did the same to the right eye. ‘Oh yeah, that’s it. I was thinking I couldn’t see straight because I’m so drunk but maybe everything’s blurred because they actually fell out hours ago. Probably on the dance floor. It got pretty loose.’

‘Okay, well, I’ll leave you to it.’

‘Night.’

Three am. I lay in an agitated half-sleep, waiting for the baby’s cry, but for once he slept on, and the longer I lay there the more anxious I felt, every bad thing that might happen to him queuing up at the bottom of the bed to present itself to me in vivid detail. Sliding under the bathwater. Falling out a window. Dying in his sleep. Forgetting to breathe. Some virus slipping into our house and stealing him away in a few panicked hours as we dithered too long over calling an ambulance and he succumbed, the exact chilling Victorian word the midwife had used in a hushed tone as she told me about his immunisation schedule. Terrible things happened to small people. I had always known this, but now there was the possibility that a terrible thing might happen to this particular small person, and as his protector, I was the only one who could prevent it. He slept on beside me, breathing open-mouthed, unaware of his many ends being played out in the head beside him.

Around four, for a bit of much-needed variety, the birth reel started up again. It played on repeat, like a visceral horror movie I’d once seen projected onto a living-room wall at a Halloween party once, except with me as the main character.

Rachel’s words about her time in hospitals had stayed with me. Had I misinterpreted the kindness of the doctors and midwives? Hade I done it all wrong? Why did I even care? Nothing would change the events of that night. So why did that movie reel keep playing?

What I wanted was for the baby to wake, so I could feed him and then fall asleep for a few hours, knowing I wouldn’t be woken. Finally he obliged, and I drifted off for a while, before I woke up to Paul, looking well-slept and alert in his ironed shirt, placing a cup of tea on my bedside table and whispering that the baby was awake beside me and wearing a clean nappy.

Around noon, the baby and I were both dressed and fed. Today, we would again attempt to re-enter the world. I quietly closed the door of the apartment, where Rachel slept on in the spare room, and took the lift down to the lobby. The man at the desk didn’t acknowledge me as I passed. As a mother, a pram pusher, I was now invisible. Strangely liberated. And lucky. For everything I might have lost – freedom, sleep, work – I had gained even more in the form of my son. Of course I had. The bad thoughts that came in the night were afraid of clear morning light, and fell silent. All we needed to do was work out how to make it all come together, somehow. And fill the hours.

We drifted through Liverpool Street Station, office workers stepping nimbly around the pram as we made our slow, lumbering way through the main concourse towards Bishopsgate, dwarfed by this brightly lit portal into world trade and international banking. Women passed in their work clothes, chatting to each other or on their phones, looking polished and rushed and always focusing on something in the distance – a train, a meeting, a deadline. I used to be like that, but now it was as if my vision had narrowed down to the perfect skin, the soft eyes, the hungry mouth of the baby. Nothing needed my attention apart from him.

A very glamorous editor in heels and red lipstick had noticed my pregnant belly at a book launch and taken me aside and said to me, very earnestly, ‘In a few months time, this tiny, magical being will come into your life and he will live with you, in your house. It’s the most wonderful thing.’

Looking at him now, I saw what she meant. The baby was still and somehow very grave in his sleep, and I realised he was a magical being, and he had come to live with me, and eventually it would all make sense, once he became accustomed to being here and I became a more competent mother.

Just then I sensed, rather than saw, Paul walking alongside a slender woman I didn’t recognise, both of them carrying bags of what might be their lunch. He looked at me as he passed and his face instantly lost its formal public expression and relaxed into the face he only gave to me, his eyes on mine intimate and kind.

‘Simone! What are you doing here?’

‘Oh, hi! We’re out getting some daylight.’

‘Look, Imogen. This is my baby!’ They peered together into the darkness of the pram as I looked her over. She was so pretty, so young, it was almost laughable – dressed in a cream silky blouse and pale pink skirt, with i

mmaculate makeup and huge eyes. Your basic nightmare, as we would have called her back in Australia.

Her phone rang and she answered it, staring at me with the curious gaze of a child.

‘Hi. Oh, yes, I rang you before. Do you realise it’s a onesie party on Saturday night? As in, we have to wear onesies?’

My eyes met Paul’s and both of us managed not to laugh.

‘Mmmm. Look, we can talk about it later, I’m with my boss and his partner.’

‘Do you have time – oh,’ he looked at his watch. ‘Sorry. We’ve got a meeting in fifteen minutes and we’re just coming back from one. Do you want me to lift the pram up the steps up for you? Where are you going?’

‘It’s okay. I’m going to wander for a bit and then head home.’

Up on Bishopsgate, the pavements were hectic with suited men and women in dark coats, but as soon as I crossed the road and turned down Brushfield Street towards Spitalfields and the ghostly white church, the air seemed to change.

Along Brick Lane, past the curry houses and burger bars and vintage clothes shops and the bowling alley, to the bagel shop, where I stopped for a salt beef bagel and a cup of tea in a styrofoam cup as the baby slept on, and then down Bethnal Green Road, towards the Museum of Childhood again. Fuelled by food and the optimism of being out in the world, I sat in the sunshine of the museum’s garden, where garish yellow and purple crocuses struggled through the bare muddy ground. The baby woke and looked up at me from the pram with his mouth opening and closing in a way that I knew signalled hunger, so I lifted him out to feed him, smiling at the small, appreciative sounds he made, like a wine connoisseur tasting a particularly good harvest. Zipped into a snowsuit, his head enclosed in a fleece-lined hood, he was a warm bundle against the cold air.

‘Mind if I sit down?’

A man, middle-aged, white, thin and tough, stood over me. He didn’t bother waiting for my reply before he joined me on the bench.

‘Name’s Brett. Who are you?’

Why did he need my name? Not wanting to provoke him, I offered it politely. His face had a hungry look, with pale, staring blue eyes, his skin cured to leather, probably by cheap alcohol and a life outside, until it stretched across his protruding cheekbones.

The Night Village

The Night Village