- Home

- Zoe Deleuil

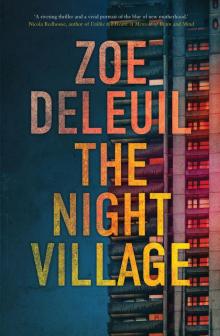

The Night Village

The Night Village Read online

Zoe Deleuil was born in Perth and studied Communications at Murdoch University. She moved to London in her twenties, working as a magazine subeditor for the BBC. Like many a sub before her, she realised while polishing other people’s copy that she would prefer to be writing her own, so completed a master’s in Creative Writing at Bath Spa University. She now works as a freelance writer, and her stories and features have appeared in Westerly, the Margaret River Press short story anthology Pigface and Other Stories, The Guardian, The Big Issue, The Australian and Green magazine, among others. Her manuscript The Back Shed was shortlisted for the 2012 Hungerford Award and longlisted for the Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award. The Night Village is her first novel.

For Felix

‘I have my dead, and I have let them go,

and was amazed to see them so contented,

so soon at home in being dead, so cheerful,

so unlike their reputation. Only you

return; brush past me, loiter, try to knock

against something, so that the sound reveals

your presence, Oh don’t take from me what I

am slowly learning …’

From Requiem for a Friend

Rainer Maria Rilke

1

Every so often I’d escape that clean, metal-bright hospital room by looking out the window. I’d stare out at the council estate across the road, at the sprinkling of powdery snow on its tiled roof. Was the snow getting heavier, or was it stalling, like me? Sometime before dawn the midwife excused herself, then returned with her arms clamped around a careless pile of white sheets. A sleepy-looking porter trailed her with a fold-out bed and set it up next to mine, and then the midwife made Paul a rough nest with the sheets and raised her eyebrows at him like he was an overtired child.

‘You need to sleep now,’ she said. But when she left the room for her break he squeezed my hand and I knew he wouldn’t rest until it was over. As we stared at each other I couldn’t believe we were about to become parents, when a year ago we were just getting to know each other.

‘Whatever you need, tell me,’ he said, close to my ear.

We’d arrived hours earlier, the lift opening onto a brightly lit hallway. In front of us was a double door with a security guard stationed in front of it. Postnatal Ward. Spelled out above another set of doors, a little way down the corridor, were the words Labour and Delivery. The letters were bold and red and impossible to miss, even as another contraction fastened around my belly like a steel claw. As I doubled over with my hand against the wall, wondering how I would ever reach those big red letters, a man emerged from the postnatal ward. He looked like someone I might have walked past at Broadway Market on a Saturday morning, a Guardian tucked under his arm. He seemed composed, if a little tired. But when our eyes met, his face crumpled in sympathy or horror or exhaustion, and he shook his head and turned away from me. It wasn’t encouraging. He veered off in the direction of the lift and I staggered towards the labour ward entrance, where Paul was already speaking to someone through the intercom. The double doors swung open and we were in a hectic waiting room with a strangely disinhibited atmosphere. In front of the rows of chairs, like a performance-art piece, a woman lay on what looked like a yoga mat, face down, knees apart. The room filled with the sound of a low, persistent alarm, and after a few confused minutes I realised it was coming from her.

As the night went on, we did laps of the ward, along deserted corridors with a hallowed Sunday-night feeling, our voices dropping to whispers each time we passed a Hasidic man who rocked rhythmically, eyes closed and deep in prayer, next to a closed door. At first my contractions were easy to breathe through, but as the hours passed they loomed over me like grey waves on a winter beach, each one harder to scale until I was exhausted and panicking. I felt like a small child again, knocked over and held down, except that it was pain and not sea water crushing me. Paul was falling apart; he wasn’t going to save me. Framed by a blue headscarf, the midwife’s serene face was my lifeboat, all that stood between me and certain death, and I kept my eyes on her until each contraction faded.

‘It’s only going to get more intense until it’s over,’ said Paul, and I tried not to swear, knowing that if I started I probably wouldn’t stop. ‘If they’re happy to give you an epidural, you should take it.’

‘Fine. Whatever works. I don’t care.’

‘Is there anything else I can do?’

‘Stop talking,’ I muttered between clenched teeth, as another wave hit.

Sometime later a man with tightly curled hair and green eyes appeared, waiting patiently for me to stop thrashing around on the bed so he could slip a needle into my spine, delivering a numbing anaesthetic that halted both the pain and the momentum of labour.

On it went, the night getting old and the snow falling outside and my blood pressure soaring higher as the epidural wore off and more people appeared, soft-focus strangers coming into the room, checking a machine that rolled out a message of mountainous lines.

I had never realised that in childbirth the baby is working with you, striving as hard to begin its life as you are to deliver it, and that you are doing this intense labour together. No-one told me that. Nor did I realise that through all the external chaos of childbirth there would be a silent centre, enclosing the two of us. We communicated – that’s not the word, exactly, because the word doesn’t exist – but I felt the baby’s intention and animal focus as it made its slow way into life.

An empty hospital crib plugged into the wall was the finishing line, waiting to be turned on at some indefinite end point. Outside was that grotty dawn that always appears after a sleepless night, and then it was Monday morning and there were more people in the room: an obstetrician and his students, another doctor standing at my side, two more for the baby, a student midwife. Finally the baby was yanked from me in two distinct pulls, a sudden blue form in the antiseptic air, landing on my belly for a second, long enough for my hand to cup the warm, wet head and slide down the slippery back, and for Paul to tell me it was a boy, before someone snatched him away and took him to a far corner of the room.

Raising my head, I looked past the faces of the obstetrician and the medical students to the two silent figures, their heads down, their backs blocking whatever they were doing in that corner. Silence. On and on and on as I stared in the direction of the baby, willing him to breathe. And then, finally, a weak yet distinct scream. I dropped my head back to the pillow and closed my eyes. The night’s grip released me and slipped from the room.

When I opened my eyes the doctor standing at my side, an Asian woman with the kind, tired face of a mother herself, smiled and said, very quietly, ‘Well done.’

‘Thank you.’

Another doctor walked towards us, holding the baby, now wrapped in a white towel. Paul held out his arms and took the bundle, and he was no longer a potential emergency, a problem to be solved. He was ours.

‘Do you want to hold him, Simone?’

Through half-closed eyes I shook my head. He was here and he was alive, and that was enough. Right now I needed to monitor everything that was still being done to me, and let my breathing return to normal. Paul gazed down at the bundle in his arms. Was he stunned, like me, that there was suddenly a baby in the room? He looked so solemn. What was it? Apprehension? A kind of despair? Was he regretting it? He’d seemed so keen. After a moment, he turned to me.

‘I should go and call my parents,’ he said, looking like he was about to pass out.

‘You can call them in here,’ I said.

‘No. I’ll step out. You did so well, Simone. I want to tell them how well you did, and that he’s okay.’

He handed me the baby and was gone.

For years I’d

dreamed of a baby, its solid fatness and cool gleaming skin, the two of us splashing in clear green water on some sunny beach. But that dream-baby was nothing like the real one that I now held. I could never have imagined such dark eyes or the tiny creaky sounds he made as he experienced his first moments of life out of water.

Everything was blurred and bleached of colour apart from him, as I watched him take in his surroundings without fear or surprise. It was as if I was an alien, recently arrived on Earth and seeing a human baby for the first time. He was the one who had just landed in the world, yet he was self-possessed and curious from the start. And I understood, looking at him, why throughout the pregnancy I had been filled with such a sense of wellbeing. He had an assurance about him, an innate calm, which I had rarely experienced before falling pregnant, but which, with him living inside me, I had been able to relax into and draw upon. Even after he was born, it was as if he had left a faint cellular trace of himself in me, so that I felt subtly altered by his stay. I knew it to be a fact, and much later on, when I began devouring articles about pregnancy and birth and child development, I read about a scientific discovery called microchimerism, which is when a remnant of DNA is left by a baby in his mother’s brain and stays there for decades after he has left her body.

Later on, I wished I could go back to that moment, or even earlier, when he was living in my belly and no-one could separate us. When it all seemed so simple. I didn’t know it then, but outside that suddenly peaceful room, someone else was waiting, too.

The labour suite was quiet now. The doctors and students and midwives had rushed away to some other woman’s bedside, taking their instruments and controlled panic with them. Swaddled under a warming lamp in the hospital crib, the baby slept, his face grave and still. The midwife, so focused and energetic and decisive during the birth, now sat by the door, deep in her notes.

Paul came back in and put his arm around me, then leaned closer, whispering into my ear. ‘I have so much respect for you, after seeing you go through that.’ He kissed me. ‘It was horrendous. So long. I didn’t think it was going to end.’

‘Me neither.’

How weird that he sat there and saw it all happen. I felt a bit jealous. I’d never been present at a birth and would have found it exciting. But he didn’t look like he’d seen something exciting. He looked wrecked. His face had that same traumatised pallor as the man I’d seen last night, staggering out of the postnatal ward.

‘I might have a shower,’ I said, suddenly keen to restore some normality.

As I got up, wrapping myself in a sheet, the midwife looked away discreetly. After everything she’d seen, it was sweet of her to afford me that dignity.

‘Try to keep your arm out of the water,’ she told me. Looking down, I saw my hand was still pierced with a pronged needle attached to a plastic box with tubes coming out of it.

I stood under the warm water, rinsing away the night, all the people who had touched me with their blue-gloved hands, and my legs shook and my arm kept drifting down into the spray. Paul appeared at the door with my bag of clothes.

‘Lift your arm, lift your arm,’ he said, again and again, but I couldn’t seem to obey him. I had no strength to hold my arm up as my whole body trembled, as if in delayed outrage at what it had been put through. Keeping my hand dry was the least of my problems. He handed me a little pink soap that I’d packed in the hospital bag, in preparation for a dimly lit water birth that I’d secretly known would never happen, and as I took it I felt like laughing.

An old friend told me how he once went on a silent retreat to some spartan forest meditation centre, where he said nothing and barely ate for ten days. On the way home he dropped in on his sister. He seemed to have lost his mind a little, because the bowls of potpourri and small animal ornaments in her living room struck him as hysterically funny. Unable to sit and converse with her as he usually would, he paced around the room, pointing at her belongings and howling with laughter, until she asked him to leave. Afterwards, part of him felt horrified by his rudeness, yet also liberated. When I saw that little pink soap I felt a bit like my friend laughing at his sister’s potpourri, except I had no energy to laugh. It was close to bliss, being so spent, and knowing that no-one expected me to do anything – because it was all done. There was only the sleeping baby, Paul and the midwife. And all three of them let me be.

Through the window I could see that more snow had fallen and the usual street noises were strangely hushed. Finding clean clothes in my bag, I dressed myself, awkward and dazed. The baby slept on under the warming lamp, larger, more real and more himself already. I stood and looked at him properly for the first time, standing back a little as if he was a famous artwork I was finally seeing in real life. I thought about picking him up but wasn’t sure if it was allowed. It seemed a ridiculous question to ask the midwife, and I didn’t know anyway if I had the strength, so I left him there.

‘We’ll move you to the postnatal ward soon, if you’re happy to go?’ said the midwife, coming over to me. ‘We’re all done now.’

‘I guess we are,’ I said, flashing back to everything that had happened here an hour or so ago. The silent huddle of medical students. The obstetrician ordering me to Look away, look away. The stirrups, the looming metal forceps. Even, at one point, a porter trying to bring in a breakfast trolley, and someone shouting at him to come back later. The whole humiliating, undignified, biological process had taken place in this room, with Paul, who by the looks of him right now should have been kept outside, pacing, like the old days, and my midwife, who did this every day.

‘Do you – do you like your job?’ I asked her.

She nodded and smiled, a little sadly. ‘I always say that ninety-nine percent of the time it’s the best job in the world, and one percent of the time it’s the worst.’ She paused, looking down, and I knew what she was referring to.

No-one spoke and I felt sudden relief as I looked at the baby, still lying in the heated crib, an angry red mark curved across his cheek. I wanted to draw him close.

Paul cleared his throat loudly, breaking the silence. ‘Let’s go, then, shall we?’ he said briskly to the midwife.

I could tell from looking at him that he wanted to tear out the door like he sometimes did when we were at home: away from me and domesticity and thoughts of work, to his favourite old English pub on Farringdon Road where he could relax among the warmth and chat of friends and strangers. He leapt to his feet and picked up my bags.

‘Yes, of course,’ said the midwife. She waited for me to sit in a wheelchair, then took the sleeping baby, bundled in his blanket, and gave him to me. An unfamiliar floating anxiety faded away the moment he was back in my arms.

The midwife wheeled me slowly through the waiting room while I held my baby like a prize, and I wondered if the labour ward had been specially designed this way, to parade all the new mothers like a motivational tool past those waiting to be admitted to the next stage of the conveyor belt of a hospital birth.

A security guard checked our paperwork and then the doors to the postnatal ward swung open. A roar of noise and stifling heat hit me first, coming from what looked like endless rows of crowded bays, each one separated by a thin blue paper curtain, every bed occupied by a mother and encircled by visitors, small children running wild in the clamour. It looked like half of East London was whiling away the afternoon here in this vast barn of a room.

The midwife wheeled me to my bed and took the baby from me, placing him in a plastic cot. Climbing awkwardly onto the bed, I could feel that the shock was wearing off, and pain was right behind it, biding its time.

‘This is insane. You’ll never sleep here,’ said Paul. ‘I’m going to ask about getting you into a private room. Or should we have you both discharged and go home?’

He looked at me, waiting for me to speak. I was about to agree with him when I noticed a man coming out of a door marked Toilet – Patients Only, still doing up his fly, and I realised I couldn’t face the o

utside world yet.

‘I think I want to stay here,’ I said. ‘They still need to check the baby. But you don’t need to get me my own room.’

He leaned over the cot. He looked sad, almost, but I still didn’t know him well enough to interpret his expressions. Normally he was contained, and his face never betrayed emotion unwittingly. If anything, he was adept at reading other people’s moods, while giving away nothing himself. But right now, he looked raw with feeling.

‘You need to feed him,’ he told me. ‘He’s hungry.’

‘Is he? How can you tell?’ Looking at the baby, I saw that he was writhing in discomfort and moving his head from side to side, his mouth open. Did that mean he was hungry?

‘I can’t, really. But you should try.’

I picked him up and tried to feed him, feeling guilty that I hadn’t noticed his distress, as Paul disappeared in the direction of the nurses’ station. While he was gone I focused on feeding the baby, positioning him as the midwife had shown me just after the birth. It seemed to work. As his jaw moved his eyes closed and he became motionless against me. After a few minutes Paul returned.

‘Okay. You’re moving to a side room now. I had to pay for it, but at least you’ll get some sleep.’

‘You didn’t have to do that, Paul. I’m fine where I am.’

Surely there was safety in numbers, and at least here I was surrounded by other mothers. And maybe once all the visitors left it would feel less frenetic. But Paul shook his head.

‘I really do think it’s better for you to have a private room. It’s no trouble, Simone. It all feels a bit much out here.’

‘Okay.’

‘Come with me.’

‘Let me try to feed him a bit more first. I think it’s working.’ And it was, somehow. I could feel his timid mouth moving sweetly against me, and the noise and chaos of the ward receded as I stared down at him, mesmerised.

Soon he was asleep again, and I got off the bed slowly, feeling swollen and weary, holding onto the plastic trolley for support. Once we had shut the door and settled into the new room, Paul seemed to relax a little, and I suddenly remembered I hadn’t told my parents.

The Night Village

The Night Village